Immigrant Children’s Friendships: Born in Poland, Growing Up in Wales

Aleksandra Kaczmarek-Day

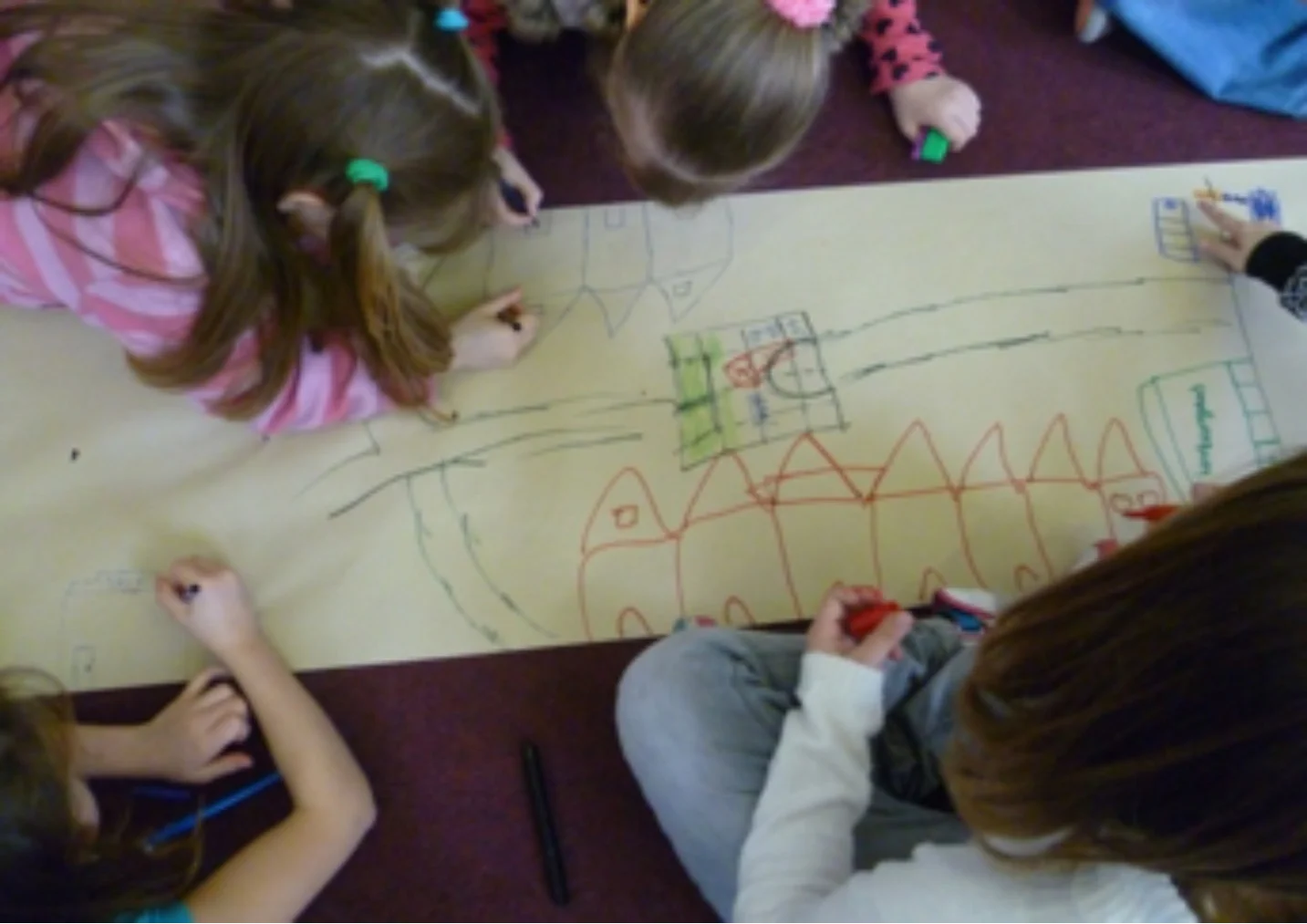

TOGETHER

Asia is Polish and Sara is Slovak and Roma. They’re both 10 years old, and are inseparable “best friends.” They take every opportunity to spend time together at their school in Wales, UK. When Asia is late for school, Sara sits on a bench to wait for her. During class and at break times, they are always together. For Sara, friendship with Asia is a serious matter. She wrote that it is equal in importance to “Mum and Slovak country” for her. Over their two-year friendship, she has become a confident Polish speaker.

They have a lot in common. Both are the oldest siblings in nuclear families and have 1-year-old baby brothers, who they adore and who feature prominently in the photo albums they bring to school. Both come from immigrant families who maintain strong intergenerational and transnational links. Asia has a cousin and an aunt in Wales; Sara has extended family across the UK. They have daily contact with people in their home countries using Internet and Skype.

Both hold a traditional view of a mother’s role. Asia explained, “My father earns money but my mum is busy, too. She has to cook dinner and manage many things every day.” The home environment is important for both. Most of the photos both girls share show them or their siblings in their rooms. Both dislike school. Asia said she won’t go to university because her mother didn’t. Sara openly stated, “I hate school, I want to stay at home.” They love going shopping for “ciuchy” (clothes). They spend time in each other’s homes and in their “plac zabaw” (local playground). They share secrets about boys and dreams of “having a boyfriend.”

Like many others, their families came to Britain looking for a “better future” after the 2004 enlargement of the European Union. During the subsequent time of increased immigration, many thousands of Eastern European children began enrolling in British schools. Immigration can be traumatic for children, uprooting them from the familiar and breaking relationship web links. Most children consider having friends to be the most important aspect of their lives, after their immediate family. Yet children of immigrant families must leave friends behind in their home countries. Rebuilding a relationship web in a new country means finding new friends. The turbulence of moving, living in an unfamiliar neighborhood, and missing left-behind family members and friends make finding a special friend even more important. Asia and Sara were exceptionally lucky to find each other.

I observed these girls and 27 others—all, except Sara, Polish-born—in my year-long study of pre-adolescent immigrant children’s friendships. This took place at two schools in Wales. I was interested in exploring Corsaro’s (1997) assertion that children contribute to their socialization through sharing and control. All 29 children considered having friends to be of paramount importance. For most, however, friendship-making was complex. Beyond the usual age, gender, and nationality limitations, they faced a range of economic, social, and linguistic barriers related to their families’ relocation and settlement processes.

US

The children told me about their friendships. The majority had a “best friend” within the school’s Polish group. Sharing mother-tongue and immigration experiences made for close bonding. “We do everything together” and “She always shares her snacks with me” were typical comments. After school, friends participated intensively in each other’s lives and homes: staying for meals, doing homework, watching television, and going to places together. Some friendships developed as a result of their parents helping each other with child care. Parents’ role in young children’s friendships shouldn’t be underestimated. As one mother said of her 8-year-old son’s social networks, “It depends on whom I am friends with.”

US AND THEM

Whereas Asia and Sara’s friendship is exceptional, and Polish-Polish friendships seem robust, Polish-English-speaking pairs of friends appear more fragile. The children eagerly wanted “English” friends to play with—as long as, like them, the children were white. They rarely initiated play with children of color. Clearly, crossing linguistic, social, and racial boundaries increased difficulties. As Corsaro (1997) notes, in verbally negotiated games, language may hinder pre-adolescents’ participation: language-learners, for instance, were innately disadvantaged in skipping-rope play. Also, members of different socio-cultural groups can misinterpret each other’s styles. Polish children hold hands and hug each other more often than other children on the playground.

For making friends outside the Polish language group, the children had different ways of bridging the cultural divide. Nine-year-old Adam, a high achiever, proudly said, “I’ve got two friends: James, who is the brightest in the whole school, and Matthew, he’s the second brightest boy in our school.” He only worried that contacts were limited to school time and class trips. Pawel, 11 years old, had four “English” (meaning Welsh) friends, who protected him, “When the bullies called names, ‘You Polish something,’ and when they were getting my goat, we stuck together with my friends and when they picked on me when we were leaving school, then we kicked them.”

JUST ALONE

Every child, however, is different and families’ circumstances vary. Some children have no siblings; some have single parents; some are shy, quiet, or peripheral and unpopular. Those who find second-language acquisition difficult are further marginalized. Children who combine these factors risk having neither Polish nor English-speaking friends. This is severe isolation.

Nine-year-old Olek, a single child living with his mother, meets no Polish, English-speaking, or indeed any other children after school. When I asked whether he visits his classmate, Alicja, also 9, he replied, “Yes, sometimes, but not always, sometimes once a week, but sometimes only once a month!” Although she has lived in Wales for two years, Alicja still hasn’t made any new friends. She loves visiting Poland and misses her friends there. After spending a winter holiday in Poland, however, she looked unhappy: “It was too cold, I couldn’t play outside with my friends.” Mikołaj, 11 years old, is on Skype every day with his “best friend,” a cousin in Poland. Despite four years in Wales, 11-year-old Darek’s three closest friends are all from his old Polish school. These children haven’t overcome their loss.

Whatever immigration’s other benefits, whether these children will truly enjoy “a better future” will be significantly influenced by their success in forging relationships.

Sources:

Corsaro, W. A. (1997). The sociology of childhood. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Rutter, J. (2006). Refugee children in the UK. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.